One of my kids’ favorite activities when we have new visitors over for dinner is to try and get me telling stories. I’ve told many of these stories so many times that the kids like to start to tell them on their own if I don’t comply with their requests. I imagine some of these stories are among the things they will take with them long after I am gone, but to ensure that they are correct (according to my flawed memory), I’ve decided to write several of the more popular ones down. These stories are true to the best of my ability to remember them. It’s possible that some of the memories have been contaminated or that my role in them has been exaggerated, but any of these types of artifacts are purely unintentional. Unfortunately, some of the names are gone from me forever, so if I leave one out, it’s either out of respect or simply because I can’t remember anymore.

My Museum Motorcycle

For as long as I can remember, I have loved anything that had an internal combustion engine. I don’t think I was quite ten when I brought home my first lawnmower engine that someone had left on the curb for the garbage man. Hoping to prevent my fascination from simply generating piles of junk motors and vehicles that didn’t run, my mom began checking out books on small engine repair from the library and leaving them somewhere I was sure to find them. As a result, I quickly became relatively adept at making old lawnmowers run. I guess I just liked the challenge of taking something broken and getting it up and running again. Besides, I was fascinated by the ability of a motor to turn something as volatile and gross as gas into power.

Around roughly this same time, my neighbor Mikey brought home a go-kart that needed lots of help. Mikey, my brother Tolon and I spent a few days working the motor over the best we knew how, and managed to get the thing up and running. All three of us loved the power that came with controlling a motorized vehicle, and we tore around the neighborhood at top-speed — somewhere around 15 miles an hour.

By the time I was twelve (it may have been ten or eleven, but I can’t really remember), I had bought an old Gemeni 80cc motorcycle from a friend and pushed it home. Against the preponderance of available evidence, I don’t think my mother believed I would get it running and consented to my buying it while hoping I would give up before I learned to ride it. She was wrong. With some help from my mom’s youngest brother Donald, I was tearing around the neighborhood on that bike within a few days. From then on, I didn’t bother with go-karts and lawnmowers unless they were broken and someone else wanted them fixed.

Over the next couple of years, I acquired a range of old, broken-down motorcycles; most of which were older than me and had been sitting in someone’s back yard for several years unmaintained. They also progressed in size and capability. The 80cc bike was successively replaced with a collection of 100cc, 125cc, 175cc, and a 360cc dirt bikes, and by the time I had a driver’s license, I think I owned somewhere around four or five of them. However, my newfound freedom to legally motor down the street spurred a desire to have a street bike. As with the dirt-bikes, one led to another, and by the time I was eighteen, mom had put a hard limit of no more than half a dozen motorcycles at any one time (I had to get rid of almost half of them).

There was one bike in all of that mix that I miss more than any of the others though. About the time I turned sixteen, my dad had a friend who was something of a modern gypsy. Mike Osbourne was an entrepreneur with a short attention span. At the time he met my dad, he was traveling from public venue to public venue selling beautifully printed and framed pages with people’s names and the origins of that name. His lack of focus, as it happened, also extended into his personal life, and he had collected a set of girlfriends across the country with whom he would shack-up when he came through town.

Somewhere back in the very early nineties or late eighties, Mike had wandered through Utah on a motorcycle he had bought new in 1983. For unknown reasons, he ended up leaving the state and leaving the bike in the care of the girlfriend who had been hosting him. However, Mike didn’t make it back to pick the bike up again for several years, during which time the girlfriend had met someone else and become engaged. Somewhere around 1992 Mike got a call from the girlfriend telling him he needed to get the motorcycle out of her garage or her fiancé would destroy it. I believe Mike was somewhere in Montana at the time, and couldn’t get there right away. He called my dad and asked if we could go get it for him. He also asked me to get it running again since it had been broken when he parked it. He promised to pay me for the work.

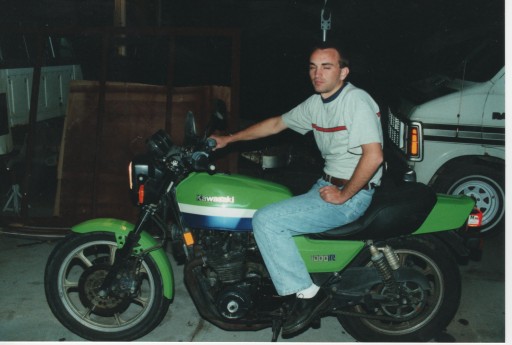

Dad had always gone out of the way to help any friend, and it wasn’t like we weren’t used to having motorcycles around, so we climbed in the van and took off for the ex-girlfriend’s house. What we found was a 1982 KZ100R painted up in the Team Kawasaki colors. It looked different… somewhere between a very muscular cruiser and a modern sport bike. I instantly liked it. We brought the bike home without incident, and a neighbor offered me space in his garage to park it while I got it running again. Over the next several months I worked it over little by little and got it up and running again, anticipating Mike’s return. The repaired bike sat in my back yard for the next two years.

Eventually, Mike came through town again. At this point, I was in violation of Mom’s motorcycle limit, and I needed to get rid of at least one of my inventory. I was also sore about the fact that I had spent a lot of time and money getting Mike’s bike running and didn’t get to enjoy any of the fruits of my labor. I gave him an ultimatum: Either he get the bike out of there and pay me for the work, sign the title over to me, or accept that I was going to place a mechanic’s lien against it and get the title anyway. At the time, he was living out of a large trailer he pulled with an old van, and didn’t have anywhere to put the bike. Seeing he had few alternatives, he ultimately agreed to just sign over the title.

Up to this point, I hadn’t done anything cosmetic to the bike. Just what needed to be done to get it running. However, once it was mine, I embarked on a two-year process of restoration that would include new paint, seat, and a totally rebuilt engine. At the end of it all, I had an almost new motorcycle (except for the scraped-up side engine cover I never got around to replacing). This bike had more horsepower than most small cars, was completely paid for, and was old enough that the insurance companies gave me a deep discount (the first modern bullet bike – the Honda Hurricane – entered production after this bike was built, and they didn’t recognize the model number as being a “fast” motorcycle). It was the best of all worlds.

The bike was amazing. It was faster than almost anything on the road. The sport bikes couldn’t match the low-end performance off the line, and the few times I caved in and agreed to race one, it wasn’t much of a competition. Because of it’s age, the speedometer stopped at 85mph, and I could hit that in about four seconds half-way up the tachometer in fourth gear. I suspected the collection of Honda CBR900s that were about hottest bike common in that area could catch me if we ever ended up on a long and straight enough section of road, but it never came down to that. The one time I really opened it up on a straight stretch was on I-80 headed west over the salt-flats.

A friend and I were riding out to Wendover, and he wanted to see if he could keep up with me on a speed-run. He had a newer Kawasaki Ninja 650 and was confident his newer, lighter, performance tuned bike would out-perform me in the top-end. We pulled off a ranch exit and agreed to launch together from the on-ramp and see how long it would take for him to catch up. We took off on the agreed signal and I didn’t see him again until I pulled off the throttle and had coasted back down under the speed limit. According to him, he had pegged out at 140 and the gap between us was still widening. When I pulled back, there was still some throttle, tach, and power left. I never did find out how fast that thing would have gone if I’d really tried. It always did anything I asked it without the slightest hesitation or complaint.

All good things come to an end, though… I got busy, then married, then broke. By fall of 1999, I was on contract to the Air Force and couldn’t find anyone to hire me for the six months I had left in civilian life. My commission-based job fixing electronics wasn’t paying well either due to mismanagement driving away our major customers. To top it all off, I was relatively newly married. I was running out of money and options. To compensate, I had started teaching lab classes and grading papers at the university, substitute teaching for the local school district, and just about anything I could find to pay the bills, but things were still very tight. I wasn’t sure how we were going to make ends meet. That’s when I started getting post-cards.

One day, out of the blue, I got a card in the mail that said in essence “we want your motorcycle.” They had listed a few specific models of “vintage” bikes they were looking for, and mine was the first one on the list. I was in no mood to sell the bike, so I quickly disposed of the card before Liz saw it so I wouldn’t have to explain why I wasn’t going to sell a motorcycle to keep us out of the red. Unfortunately, whoever had sent that card was persistent, and Liz got the mail the day the next one arrived. I was greeted with a look that meant “you know what you have to do,” as she handed me the card.

I ended up calling the number on the card, and the man on the other end started reading off the VIN number to me to make sure I had the bike he was looking for. Without knowing anything about the condition of the bike he offered me $5000 for it. I was stunned, but I also didn’t want to sell the bike. I waffled and told him I had spent a lot of time and money fixing it up. He offered $6000. Liz was oblivious to what was going on over the phone, but I think the look on my face told the whole story. All I could manage was to tell him I didn’t really want to sell it, but that I would call him back in a couple of days.

After talking it over with Liz, I agreed the right thing to do was to sell it. I wasn’t even riding it at the time since I couldn’t afford the insurance and registration fees (which were actually minuscule). I called back the next day and he offered $6500 if I could have it to the shipper in two days. I agreed, but with heavy heart. The next day I pulled it out of the shed in my Mom’s backyard where I had been storing it, took it for one last ride, then drove it up to the shipping company where they were strapping it to a pallet and loading it into a truck as I signed over the title. From what I understand, it was bought by a private museum somewhere in Houston. I’ve contemplated finding that museum and seeing it again, but all that would do is make me want it again. I think I’ll let it stay as a memory instead.

The money paid the bills until I commissioned and went active duty, something I had been stressing over for a while at that point. In our family, we chalk this up to a case where faith and paying tithing results in miracles. I still miss that bike, but in the end, getting rid of it was the right thing to do. I probably would’ve killed myself on it if I’d kept it much longer anyway. I was too fearless, and it was too capable.