As with any of my stories, this is true and accurate only to the extent that my memory is correct. This is an account of things as I remember them.

Lightning Strikes and Skinny Dipping

From as far back as I can remember, I have loved opportunities to escape civilization and make my way into the wilderness. Growing up in Utah, there were plenty of opportunities to do so, ranging from the High Uintah wilderness area a few hours east to some of the emptiest high desert on the continent to the west and south. As a kid, my mother’s family made annual trips to both the mountains and to a set of sand dunes southwest of town. These trips set a precedent that would forever shape my perceptions of what a vacation was supposed to be. Instead of dreaming of Las Vegas, Disney World, or the Bahamas; any time I had the opportunity, I would load up what I needed and make a break for the desert, the mountains, or both. Many of my better memories growing up revolve around camping out in the bush. Whether it was with my family, Boy Scouts, or friends, I always felt at ease far away from the conveniences of modern life.

One of the things that attract me to the wilderness is the very real sense of the power and majesty of nature. One of the most visible aspects, and one I love to watch, is lightning. Now, I don’t have a lot of first-hand experience with lightning other than watching it as a storm rolls through, but that on its own can be quite powerful. One of the most incredible experiences I can remember was watching, hearing, smelling, then being enveloped by a thunderstorm that rolled across the west deserts of Utah to overtake and nearly drown our camp outside Delta. If you’ve never experienced the feel and smell a desert thunderstorm soaking parched ground, there is no hope of explaining what it’s like. I’ll never forget the rolling thunder and flashing bolts as we watched them approach from many miles away. However, I do have a couple of rather close experiences with this particular expression of nature’s power — both of which occurred in the four-lakes basin of the High Uintah Wilderness Area.

Over the course of several camping and backpacking trips through the Uintahs, I learned that the weather at altitude is highly unpredictable – especially in the summer. Many times I’d been caught in a hailstorm when only minutes before the sky was clear and the air was warm. Not wanting to be caught unprepared, I made it a point never to sleep under the stars, putting a tent between me and the rain if at all possible.

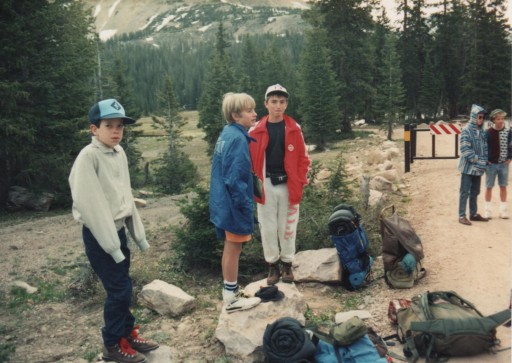

On my first backpacking trip into the four lakes basin, things had been completely unremarkable other than the scenery. We had arrived at the camp site happy to be at a point where we could stop for a few days rest, and we immediately began setting up camp. I chose a spot in the shade of several large pines with a soft layer of needles covering the ground and set up my tent, feeling quite happy with my selection. The remainder of the day was spent goofing off or fishing without incident. I went to bed tired and happy.

Somewhere in the night, a powerful storm rolled in bringing hail and lightning with it. I awoke to flashes of light, crashes of thunder, and the sound of hailstones bouncing off of my tent. As I laid there watching and listening to the power of nature, there was a blinding flash accompanied instantly by a deafening crash of thunder. My hair stood on end, and before I could react, I heard the sound of several things much larger than hailstones hit my tent and the ground around it. I wondered what it was, but didn’t dare go out until the storm had passed. The next morning, after watching the sunrise through the golden color of my tent fabric, I crawled out of my sleeping bag, unzipped the tent, and found a large piece of tree bark resting on the rain fly with several large chunks of green wood scattered all around. Lightning had struck a tree only a few feet away and literally blew it apart. Nature’s power is awesome, and I felt blessed that I hadn’t shared the fate of that all too nearby tree.

The basin we were in was right on the main trail, and while remote, was rarely unoccupied. The heavy traffic brought lots of fishermen competing for the limited stock in the lakes. Consequently, fishing wasn’t particularly good, and as young men, the thought of depending on a couple fished out lakes for food wasn’t something we looked forward to. After most of a day trying to make due with the played out lakes, several of us took a hard look at the map and decided to hike over “cyclone” pass and along an unmarked trail to a remote lake to see if the fishing would be better where there had been less traffic.

Cyclone “pass” wasn’t much of a pass. Rather, it was more of a saddle between two high peaks, with even the lowest part of the saddle above the tree-line (roughly 10K feet). Once over the pass, the trail on the map disappeared, but the lake would be easy to find by following the ridge-line north a few miles from the pass. We took off with minimal gear and supreme confidence in our abilities. We climbed over the pass, pausing only briefly to catch our breath and enjoy the spectacular views, then dove into the unmarked wilderness. After several miles of jumping between Volkswagen Beetle sized boulders we arrived at Thompson lake. The fishing was awesome, and we limited out within a few hours. The hike back to camp was uneventful, if tiring. We had caught enough fish to feed us for the rest of our stay in that area, and the rest of the trip was beautiful and drama free.

When our Scout troop returned to the four lakes basin the next year, there was a group of guys who wanted to head back over to Thompson lake and see if the fishing was as good as it had been the year before. I don’t fully remember the reasons why, but I decided not to go with them. If memory serves, I think I was feeling kind of sick and wanted to rest rather than tackle the steep climb up the pass and the mountain-goat version of a trail once I got to the other side. In any event, I was one of a few people who stayed back at camp and watched as everyone took off to head up the pass.

Several hours later, a black cloud rolled in with threats of a flash thunderstorm. Almost as soon as this cloud arrived, enormous thunderclaps reverberated through the trees and across the basin. I was glad to be under cover of a rain fly instead of out on the trail, and was sitting back enjoying the sound of the storm when a handful of guys came trotting out of the trees through the rain. They had been on their way back to camp when the storm rolled in. As a matter of fact, they were nearing the top of the pass when they first saw the darkening skies. The ones we saw coming out of the trees had decided they weren’t comfortable standing exposed above the tree-line with a storm rolling in, and had taken off at the best speed they could make to get out of the open.

A few, however, had decided that they weren’t in any danger, were too tired to run with their packs, and thought it would be neat to watch the storm from their vantage point at the top of the pass. Apparently it hadn’t occurred to them that a graphite fishing pole sticking up out of a pack would make a pretty good lightning rod. As they were standing up on the pass watching the storm flash and crash, lightning struck close enough to daze them and make all their hair stand on end. These few, who had been too tired to jog down the hill earlier, sprinted all the way to camp. By all accounts, the lightning struck within a few feet of Tommy Mosier. He looked very rattled when he got back to camp, and I doubt he ever took another chance with being out in the open during an electrical storm.

As with the previous trip, the remainder of the hike was fantastic as we hiked from lake to lake on a fifty mile trek. However, a full week on the trail doesn’t make for the most fantastic of personal hygiene conditions. By the time we made the last overnight stop at Granddaddy lake, we stank, and we knew it! The thought of going back into town smelling and looking like we did didn’t appeal to us. Since we were still several miles inside the wilderness and hadn’t seen anyone for several days, and since we had a full day to rest at the lake before we hiked out to the trail-head the following day, we decided to strip down, wash our clothes in a creek, and jump in the lake to wash off the worst of the stink and dirt.

Something to understand about the lakes and streams in that area is that they are all snow-fed. Even in late August there can still be pockets of snow and ice in shady areas. As a result, the lakes are rarely, if ever, much above freezing. Jumping into one of them is likely to cause an involuntary contraction of every muscle in your body followed by some form of audible exclamation. Jumping in to get clean is a very rapid process… wet, rub, rinse, then climb out and into the sun to dry out and warm up.

We had stripped down, washed our clothes and hung them out to dry, and were just getting into the water to clean up when a large group of young women came trundling up the trail and into view. Everyone in the water sunk down to their necks in an attempt to stay modest while we waited for them to pass. Unfortunately for us, they didn’t just continue down the trail. Apparently they had noticed us, and had slowed down to gawk at the spectacle. By this point, I was getting horribly uncomfortable as various parts of me either turned blue or shrank into nothingness. As near as I could tell, they wanted to see something they weren’t seeing with us hiding in the water, wouldn’t leave until they saw it, and I was tired of being cold and wet. I stood up in all of my naked glory, smiled, and walked right through the line of girls who had stationed themselves between us and our camp, greeting them with something stupid like “hello ladies,” or “water’s fine, care to join us?” as I passed. I’m certain they were more embarrassed than I, but I doubt they were more mortified than my scout master.